Michael Li is senior counsel at the Brennan Center for Justice.

Voters are increasingly turning to state constitutions to fight partisan gerrymandering. Will the Kentucky Supreme Court be the next to greenlight such claims?

UPDATE: On December 14, 2023, the Kentucky Supreme Court affirmed the constitutionality of the state’s congressional and legislative maps. The ruling held that while partisan gerrymandering claims were justiciable under Kentucky’s constitution, the maps did not violate any of the constitutional provisions invoked by the plaintiffs.

In particular, the court declined to follow the Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s 2018 ruling that its state’s constitution’s free and equal elections clause — which served as the basis for Kentucky’s analogue — prohibited partisan gerrymandering. Instead, the Kentucky Supreme Court adopted a much more narrow interpretation of the state’s free and equal elections, holding that since the “apportionment plans do not restrain or coerce the casting of any votes,” they “do not infringe on the guarantee of free elections.”

The court similarly ruled that the plaintiffs’ equal protection claims were subject only to rational basis review since the maps did not interfere with the plaintiffs’ ability to cast a ballot and that they did not run afoul of the constitution’s guarantees of freedom of speech and assembly because the maps “[did] not in any limit the ability of the people to freely communicate their thoughts and opinions or otherwise speak, nor to assemble or associate for political purposes.”

The court also held that the maps did not violate the state constitution’s guarantee against arbitrary government and that number of county splits in legislative maps “[did] not rise to the level of a clear and flagrant disregard” of rules limiting such splits.

One justice dissented, saying that he would have dismissed all of the claims for lack of standing, while another said he would have found most of the plaintiffs’ claims to be non-justiciable political questions. Only one justice said she would have ruled for the plaintiffs on some of their claims.

On September 19, the Kentucky Supreme Court will become the latest state high court to consider the question of whether legal challenges to gerrymandered voting maps are justiciable under its state constitution.

The U.S. Supreme Court controversially ruled in 2019 that partisan gerrymandering claims were non-justiciable “political questions” under the federal constitution, but said “our conclusion [does not] condemn complaints about districting to echo into a void . . . State statutes and state constitutions can provide standards and guidance for state courts to apply.”

So far, voters have had better luck in state courts. Since 2018, state trial or appellate courts in eight states have ruled that gerrymandering challenges are actionable under various state constitutional provisions, though courts in North Carolina have since reversed course. Only the Kansas Supreme Court, now joined by North Carolina’s high court, have followed the U.S. Supreme Court in holding gerrymandering claims to be non-justiciable. (State supreme courts in New Hampshire and Utah also are currently considering the question of justiciability.)

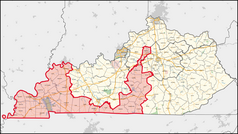

The case before the Kentucky Supreme Court, Graham v. Adams, arises from the contentious redrawing of the state’s legislative and congressional maps after the 2020 census. A group of Democratic voters and the Kentucky Democratic Party say the resulting state house and congressional maps intentionally lock-in durable pro-Republican advantages for the balance of the decade.

By aggressively skewing maps, the challengers argue GOP lawmakers ran afoul of multiple provisions of the Kentucky Constitution.

Similar to many of the partisan gerrymandering cases in other states, the challengers contend that drawing maps to favor one party over another violates the state’s “free and equal” elections clause as well as Kentucky’s more unique prohibition on the exercise of “absolute and arbitrary power over the lives, liberty and property of freeman” — two provisions with no analogue in the U.S. Constitution.

In addition, they argue that the gerrymanders violate the state constitution’s guarantees of equal protection, free speech, and the right of assembly, arguing that those provisions should be construed more expansively under Kentucky law than their federal equivalents. And as is often the case in litigation over maps in state court, the challengers also are asserting a more mechanical claim: namely, that, in the course of creating their gerrymander, Republican map drawers excessively split counties in the state house map in violation of state constitutional provisions designed to minimize such splits.

The gerrymandered maps, which passed over the veto of Gov. Andy Beshear (D) and largely on a party-line basis, had a dramatic effect. In the 2022 midterms, Democrats won only 20 of 100 seats in the state house of representatives — a record low — with multiple incumbent Democrats losing election in radically reconfigured districts. Republican House Speaker Jeff Hoover credited his party’s enhanced majority to the new maps in a celebratory tweet that has since come to feature prominently in the lawsuit over the maps.

Congratulations to House Republicans on significant gains, yet again. Majority of credit must go to @tommydruen architect of redistricting maps! He won’t take credit, others won’t give him the credit, but make no mistake…80 doesn’t happen without his work. Well done my friend!

— Jeff Hoover (@buckethoover) November 9, 2022

The effects of the new congressional map were less striking but still significant. Under the new map, lawmakers transformed the First Congressional District (KY-01) into a highly non-compact and noncontiguous district that joins voters in more Democratic-leaning parts of central Kentucky with solidly Republican counties in the southern and western parts of the state. The result was a district where experts found Democratic candidates were unlikely to receive more than 35 percent of the vote. By contrast, had voters in central Kentucky been placed in a more compact district, the district would be one that would be competitive for Democrats under the right circumstances.

A state district court held a trial and found in November 2022 that while the plaintiffs had compellingly established factually that both the state house and congressional maps were partisan gerrymanders, and that the plaintiffs had standing to bring the suit, “the Kentucky Constitution does not expressly prohibit partisan gerrymandering in redistricting and does not require the General Assembly to minimize the number of times that the required split counties are further divided.”

The district court notably declined to give any weight to partisan gerrymandering decisions from other states interpreting analogous provisions, but instead said it would base its decision on debates around ratification of Kentucky’s 1891 constitution and state law precedents.

The challengers appealed the ruling to the state’s intermediate appellate court, but in March the Kentucky Supreme Court agreed to hear the case without waiting for that court’s ruling. (Kentucky also is seeking reversal of the district’s findings that the maps were factually gerrymanders.)

It’s still too early to know what impact a favorable ruling for the plaintiffs from the Kentucky Supreme Court might have on the 2024 elections. The Kentucky case is unusual in that the question of the justiciability of partisan gerrymandering under the state constitution is being taken up only after a full trial on the merits and after a determination that the maps are, in fact, gerrymanders. If the court rules that one or more of the plaintiffs’ claims are justiciable and upholds the district court’s factual findings, questions of liability will have already been resolved. The only real question would be whether there is enough time to redraw maps in time for Kentucky’s May 2024 primaries.

So far, comparatively few of the state court wins against partisan gerrymandering have been in the South. A victory at the Kentucky Supreme Court would be big not only for Kentuckians but would offer hope — and a potential model — for voters across the highly gerrymandered region.

Michael Li is senior counsel at the Brennan Center for Justice.

© 2024 Brennan Center for Justice at NYU Law

Related Commentary

State Courts Can and Should Do More to Protect Voters

State constitutional clauses collectively elevate the status of voters as a group, giving state courts a strong reason to use a separation of powers analogy against efforts to curtail voting rights.

Montana Strikes Down Voting Restrictions

At issue was a series of state laws passed in 2021 that created new hurdles for voting, such as eliminating Election Day voter registration and a ban on paid absentee ballot collection.

Who Has the Authority to Prosecute People Accused of ‘Voter Fraud’ in Florida?

A Florida appellate court is set to determine whether a statewide office created in the 1980s by constitutional amendment to combat organized crime can prosecute someone accused of voting while ineligible.

Texas Supreme Court Set to Consider Legislative Interference in Elections Administration

The case concerns the constitutionality of a law that abolishes the elections administrator position in just one county.